Along with much of the American and British public in the mid-19th century, Charles Francis Hall was riveted by accounts of Sir John Franklin’s tragic 1845 expedition in search of the Northwest Passage, the fabled Arctic sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The scale of the loss—two vessels and 129 men—and the mystery surrounding the fates of Franklin and his crew, prompted many expeditions that set out to discover the outcome of their story.

“Hall was a deeply eccentric man, perhaps the unlikeliest fellow to ever become an Arctic explorer,” said Russell A. Potter, a professor at Rhode Island College. Hall had no more than a few years of education and lived a quiet life as a family man and modestly successful engraver and publisher in Cincinnati, Ohio. But his interest in Franklin’s doomed quest turned into an obsession with the Arctic and a personal mission to find survivors.

By the late 1850s various expeditions had found bodies and relics from the Franklin crew, dimming hopes of finding anyone alive. Still, in 1860, the 39-year-old Hall left Ohio for the Arctic to see if there were any lives left to save.

(Arctic shipwreck found "frozen in time.")

Victim: Charles Francis Hall

Hall undertook two trips to the Arctic during the 1860s. He found no survivors from the Franklin party, but he lived among the Inuit people for nearly eight years and documented their culture more than anyone had before him.

When he returned to Washington, D.C., in 1869, Hall had his sights set on going to the North Pole, which had replaced the Northwest Passage as the chief goal of Arctic explorers. Apart from the costs of finding the passage, many believed it could never be a viable commercial waterway. Hall lobbied hard for his expedition, winning the backing of President Ulysses S. Grant.

Congress authorized $50,000 for the voyage, making it the first Arctic exploration entirely funded by the federal government. A screwpropelled steamer used by the Union side in the Civil War was retrofitted for the Arctic ice. The hull was reinforced with oak, and the bow sheathed in iron. Renamed U.S.S. Polaris, it set sail from New York on June 29, 1871, with 25 crew members, among them Inuit guides Ipirvik and his wife Taqulittuq, as well as their infant son. In Greenland, Inuk guide and hunter Hans Hendrick and his family joined the crew.

Polaris power struggles

Hall knew how to survive in the Arctic but not how to run a fullfledged expedition. He was a commander with no military or naval rank, and a captain with no navigational experience. In the end, Sidney O. Budington acted as navigator, with George E. Tyson as assistant navigator. The vessel’s command was split three ways.

Another source of division soon materialized in the form of a German scientific team also on board, led by scientist and surgeon Emil Bessels. He was a 24-year-old graduate of the University of Heidelberg’s medical school. Bessels and the Germans held little respect for the uneducated Hall.

After a month of sailing, tension and conflicts were growing. As Tyson would later write, “Some of the party seem bound to go contrary anyway, and if Hall wants a thing done, that is just what they won’t do. There are two parties already, if not three, aboard.”

(Arctic obession drove explorers to seek the North Pole.)

Sudden death

Meanwhile, the Polaris advanced, reaching latitude 82° 29' N, the first ship in history to sail that far north. That, however, would be as far as the ship would get. Turned back by ice in the Lincoln Sea, the Polaris put in for the winter in northwestern Greenland, a spot Hall called “Thank God Harbor,” about 500 miles south of the pole.

On October 24, 1871, Hall returned from a two-week sledge journey to the north. He drank a cup of coffee and became violently ill with symptoms that included delirium and partial paralysis. Bessels diagnosed his condition as apoplexy (a stroke).

Meanwhile Hall insisted that Bessels was trying to poison him. He even banned the doctor from his bedside between October 29 until November 4, during which time his condition improved. Hall then allowed Bessels to resume treatment. He seemed better, even taking a walk on deck, then suffered a relapse and died on November 8, 1871. His body was buried nearby.

Arctic castaways

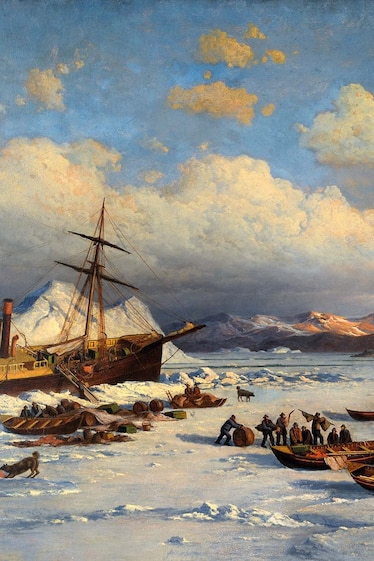

Budington, now the ship’s leader, had no interest in reaching the North Pole, calling it “a damned fool’s errand.” Once the ice cleared, the ship headed south on August 12, 1872. Two months later, when Polaris ran aground on a submerged iceberg, Budington ordered cargo to be thrown onto the ice to buoy the ship.

That night, 19 members of the expedition, including Tyson and all of the Inuit, were on the ice pack nearby when it suddenly ruptured. In the blackness of night, the ship broke free, leaving them stranded on the floe. Before long, the ship, with 14 crew members (including Budington), and the party on the floe lost contact. Cast adrift for more than six months, the group was rescued from the floe by a whaler off the coast of Labrador. If it were not for the Inuit among them, who hunted from the floe’s edge, they would not have survived.

Meanwhile, the 14 survivors on the Polaris experienced their own odyssey. With coal stores running low, Budington decided to run the ship aground near Etah, Greenland. The crew built a hut there, and the local Inuit helped them survive the winter. The crew then built two boats out of wood from the Polaris and sailed south. They were rescued on June 23, 1873 by a whaler off Cape York.

Murder motives

The Navy held an inquiry into Charles Francis Hall’s death, but with conflicting testimony, and no body for an autopsy, no charges were made. Clearly there was little incentive to add scandal to an already disastrous outcome.

Nearly a century after Hall’s demise, Arctic historian Chauncey C. Loom is investigated the mystery, which he recounted in Weird and Tragic Shores: The Story of Charles Francis Hall. In 1968 Loomis had Hall’s body exhumed. Analysis revealed that he had received large doses of arsenic in the two weeks leading up to his death. Arsenic was common in medical kits at the time but was never given in such quantities. Loomis considered Budington, who dreaded the journey north, as a suspect. However, the arsenic had been administered to simulate apoplexy, which Budington would not know how to do.

Loomis concluded that Bessels was the only one with the skill to murder Hall, but a clear motive was lacking. Bessels was openly dismissive of Hall, who returned the favor by calling him “the little German dancing master.” But Loomis’s opinion was that personal dislike was too weak a motive for murder.

Another piece of evidence emerged in 2015, when Russell Potter, the Rhode Island College professor, came across an envelope postmarked October 23, 1871, and addressed by Hall to 24-year-old Miss Vinnie Ream, a talented artist who had been commissioned to make a statue of Abraham Lincoln when she was 18. Before sailing on the Polaris, both Hall and Bessels socialized with Miss Ream in New York.

Potter knew there had been correspondence between her and Bessels that suggests a romantic connection. Miss Ream also sent a bust of Lincoln to Hall, which he placed in his cabin on the Polaris. Potter theorizes that a love triangle might have been at the root of Hall’s death. “The additional motive for Bessels makes the case a strong one,” said Potter, “but absent a time machine, I don’t think it can ever be 100 percent resolved.”