Jurors trooped past a gaggle of anxious journalists and bystanders as the superior court in New Bedford, Massachusetts, began what would be considered the crime of the century—the 19th century. The defendant was no movie star, super athlete, or international spy. She was a Sunday school teacher, accused of murders so gruesome that they are still the stuff of legend more than 130 years later. Armchair experts and scholars alike continue to debate: Did she, or didn’t she? It’s a good bet they’ll never find out.

The murders

The enigmatic woman at the center of the case was Lizzie Borden, who stood accused of murdering her father, Andrew Borden, and stepmother, Abby Borden, with an axe. Lizzie’s trial attempted to answer the question of her guilt—but along the way, it raised many more. Over a century later, public fascination with the grisly murders and Lizzie’s innocence or guilt hasn’t faded.

By all accounts, the life of Lizzie Andrew Borden, an unmarried 32-year-old woman who lived with her sister Emma, father, and stepmother in Fall River, Massachusetts, was uneventful. Her father, Andrew, had grown rich first making and selling furniture and then investing his earnings in real estate. Despite his wealth, Andrew continued to live frugally.

(Was the ‘Colorado Cannibal’ a villain or a victim? You decide.)

Lizzie and Emma’s mother, Sarah, passed away in 1863. Three years later, Andrew married Abby Durfee Gray. Most accounts say the relationship between Abby and her stepdaughters was cordial but never warm or affectionate. Church-going and prosperous, the Bordens were community fixtures living quiet and respectful, if unremarkable, lives.

That changed on August 4, 1892, when Lizzie’s cries rang through her family’s house late that Thursday morning. She had discovered her 69-year-old father’s bludgeoned body on the couch in the family parlor. Further investigation upstairs yielded her 64-year-old stepmother’s body, maimed and lying dead on the floor of the guest bedroom.

Fear spread through the town of Fall River. The murderer felt bold enough to strike in broad daylight just a few blocks from a busy business district. Nothing was stolen from the house, and neighbors had neither heard nor seen anything suspicious that morning. Whispers began to circulate that the murderer might not have been an intruder at all, but someone closer to home.

(Ghost stories scare up new life at these historic hotels, including the Borden house.)

Trial of the century

Within days, the entire nation was aflame with the news of the murders and potential suspects. On August 4 Emma was 15 miles away, leaving only Lizzie and the maid, Bridget Sullivan, at home. When questioned by police, Lizzie gave inconsistent accounts of her activities and whereabouts. Soon the spinster Sunday school teacher was the lead suspect.

After an inquest, authorities indicted and jailed Lizzie. Ten months later, in June 1893, the trial began with prosecutors accusing Lizzie of killing her stepmother with at least 18 blows to the head with a hatchet, then seeking out and murdering her father with another 11.

Almost immediately, the trial focused on whether Lizzie, an upper-class woman, was capable of committing the crimes—and whether her relationship with her parents was respectful or acrimonious. Testimony revealed that Lizzie and Emma lived increasingly separate lives from their parents, eating by themselves and inhabiting their own wing of the house. Witnesses reported Lizzie had referred to her stepmother as a “mean old thing,” and that when questioned about her mother’s death immediately after the murder, Lizzie had corrected the police officer, reminding him that Abby was not her mother by birth.

And then there was the poison. A druggist testified Lizzie had attempted to purchase poison before the murders, telling him she needed prussic acid to keep moths from eating a fur cape. The druggist didn’t give her the poison, and an investigation yielded no evidence of poison in the murdered Bordens’ stomachs. But prosecutors claimed Borden had committed the murder “not by the pistol, not by the knife, not by arsenical poisoning. There was but one way of removing that woman [Abby Borden], and that was to attack her from behind.”

Media circus

The Borden trial turned Fall River, Massachusetts, into a reporter’s paradise—and journalism on its head. Lurid, speculative, sensational, even fictitious accounts of the crime and the subsequent trial were common, as reporters from as far away as San Francisco competed with each other for compelling coverage of the double murder. Their stories sold out nationwide and turned “Miss Lizzie” into a household name. Public interest in the crime was so intense that the Boston Globe paid $500, a fortune at the time, for a story that painted Lizzie as a disgruntled daughter whose conservative father had disowned her after she became pregnant out of wedlock. It was complete fiction—and its author, fearing legal repercussions, fled to Canada, only to fall to his death while boarding a train.

Thanks to a nearby telegraph booth and the presence of dozens of reporters, the public gobbled up every iota of evidence and tidbit of testimony. “It became the drama everyone wanted to follow,” says Karen Roggenkamp, an English professor at Texas A&M University-Commerce and author of Lizzie Borden: Spinster on Trial, which covers the effect the sensational trial had on the press and the American public back in 1893. Borden was a national celebrity, and people scrutinized her clothing, demeanor, and gestures as she took in the proceedings from the defendant’s box.

Testimony and evidence

On the eighth day of the trial, onlookers were horrified by one of the only pieces of physical evidence offered by the prosecution: plaster casts of both parents’ mangled skulls. Lizzie left the room during the medical examiner’s explicit testimony. She was gone when the examiner claimed the crime could have easily been committed with a household axe and by a female assailant of average strength.

In Lizzie’s favor was that two key pieces of evidence were never found: the murder weapon and bloody clothing worn by the murderer. Lizzie was accused of burning a dress after the crime, but her sister testified it was an old, paint-covered garment that was taking up space in their shared wardrobe.

Police had been in and out of the Borden residence for days following the murders, leading to an outcry about improper evidence gathering. The prosecutors did not present a definitive murder weapon—a key weakness exploited by the defense, who claimed the murder was either the work of a random peddler or an acquaintance who resented the Bordens’ prosperity and social standing.

As the trial wrapped up, the prosecution acknowledged that much of its evidence was circumstantial, from an underskirt with a minute drop of blood on its hem to police testimony that Lizzie said Abby was not her real mother. But during closing remarks, prosecutors told the jury that didn’t matter. “There is scarcely a fact that is not incriminating to Lizzie,” said district attorney Hosea Knowlton.

The defense reminded jurors of Lizzie’s “spotless” life. “You have wives and daughters,” entreated attorney and former Massachusetts governor George Robinson. To find her guilty would “be so deplorable an evil that the tongue can never speak its wickedness.” But perhaps more important was the reminder that “there is not one particle of direct evidence in this case from beginning to end against Lizzie A. Borden. There is not a spot of blood, there is not a weapon that they have connected with her in any way, shape or fashion.”

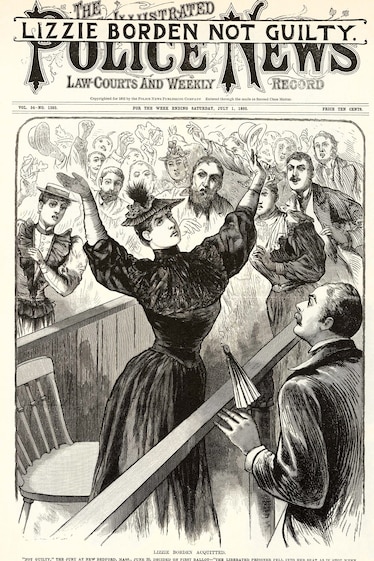

Though the judge had declared her “probably guilty” at her earlier indictment, the all-male jury found Lizzie Borden not guilty after deliberating for just one hour. As the verdict was read, Borden fell into her chair, covered her face, and sobbed.

The verdict

Lizzie had been acquitted, but the court of public opinion thought otherwise.“The community pretty quickly turned against her,” says Roggenkamp. Her decision to remain silent at trial earned almost universal condemnation at the time, Roggenkamp explains. “The fact that she didn’t speak to people about [the murder] upset them horribly.” The stoic Lizzie resumed her life, refusing to speak further about the murders. And the legend—and mystery—grew.

Even now, would-be detectives speculate about the real story of the murders. Did Lizzie attempt to poison her parents? Had Lizzie nearly been murdered herself by a culprit who fled when they realized she had discovered her parents’ bodies?

(Everyone knows the story of Jack the Ripper. This is the story of the women he murdered.)

Given poor evidence gathering, overblown press coverage of the time, and Lizzie’s own contradictory statements before the trial, says Roggenkamp, it’s unlikely anyone will know for sure. “There was certainly enough reasonable doubt to acquit,” she says. “Buthow [Lizzie] chose to react certainly didn’t help her case.”

Guilty at the ballet

Old and young

Then there’s the mystery of why a 135-year-old murder remains so fresh in the public’s imagination. Part of its lurid appeal is undoubtedly the nature of the crime. But for Roggenkamp, the mystery of Lizzie Borden herself helps explain the lengthy afterlife of the crime. “She didn’t speak about it,” says Roggenkamp. But she didn’t leave Fall River either; she just resumed her life as town scapegoat and local enigma.

“Everyone loves a mystery,” says Roggenkamp. And in the meantime, Lizzie has become “an empty vase” for other people’s ideologies, obsessions, and theories—that won’t be waning anytime soon.

(This Arctic murder mystery remains unsolved after 150 years.)